Updated 17:10 PM PHT Fri, June 1, 2018

Venice, Italy (CNN Philippines Life) — Artist Yason Banal admits he questions the idea of “Freespace” — the theme of this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale — itself. Banal, whose work is at the center of the Philippine Pavilion’s “The City Who Had Two Navels,” doesn’t hesitate to question the institution that has given him a chance to showcase his work here; for him, it is a criticality needed when working within a venue as large as the biennale.

From the context of the biennale, it seems like an ideal jump-off point for global discussion as to what constitutes a “freespace.” This year’s artistic directors Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara of the Dublin-based Grafton Architects is keen on making small ripples of criticality in this large, sprawling event that runs for six months and gathers some of the best talents in the stellar world of architecture. In their manifesto, their edition of the biennale “will present for public scrutiny examples, proposals, elements — built or unbuilt — of work that exemplifies essential qualities of architecture which include the modulation, richness and materiality of surface; the orchestration and sequencing of movement, revealing the embodied power and beauty of architecture.”

In the Giardini, one of the two venues of the Venice Biennale where most of the first world pavilions are, the idealized “freespace” are sometimes empty spaces, like the British, Swiss, and the Greek Pavilions, where discussions will arise from the questions that their respective emptiness will point out, though some are more successful than others.

But in the context of a “developing country” such as the Philippines, Banal asks, “What does ‘freespace’ mean in a postcolonial state with strong undercurrents of feudalism, authoritarianism, and transglobal capitalism? How is the neoliberal landscape of openness, transparency, and fluidity connected to the market forces, surveillance systems, and creative expressions?”

“The City Who Had Two Navels,” curated by Edson Cabalfin is a study on how two navels — the forces of colonialism and neoliberalism — have shaped the way we live in our cities. The pavilion features works from UP Diliman, De La Salle – College of St. Benilde, University of San Carlos, UP Mindanao, TAO Pilipinas, a women-led architectural NGO; as well as artist Yason Banal and photographers Marvin Maning and Jinggo Montenejo. Cabalfin also commissioned individuals to contribute videos that chronicle their lives in urban cities.

The pavilion’s outer wall is covered with LCD T.V. screens, scale models, photographs, and video installations contributed by UP Diliman, De La Salle – College of St. Benilde, University of San Carlos, UP Mindanao, and woman-led architectural NGO TAO Pilipinas among others. Photo by DON JAUCIAN

Ten minutes away from the Philippine Pavilion at the Arsenale is the “main” biennale venue, the Giardini where our former colonial master, Spain, the Pavilion of which gathers works, proposals, responses, and criticism from the country’s architecture students from 2012 to 2017. A few minutes walk is the U.S. Pavilion, embroiled in its discussions on race, humanity in the face of data collection, and architectural impact of politics and environment. The Japanese Pavilion is at the Giardini as well, its pavilions covered in architectural drawings which ask visitors to think about and feel their response to the works on display.

The Philippines, on the other hand, seemingly still hasn’t moved on from our colonial past, and trapped in the notions of free market posed by prevailing economic forces such as the U.S. and the U.K. And this is what our pavilion, “The City with Two Navels,” proposes: Where will Philippine architecture go while we’re still in the claws of these insidious forces?

In separate interviews, CNN Philippines Life spoke to curator Edson Cabalfin and artist Yason Banal to talk about the design of the pavilion, collaborating with the architectural schools for responses to colonialism and neoliberalism, and why we should remain hopeful about our country.

“If you don’t even know what the question [is] then how can you even dismantle it. How can you even have a revolution when you don’t even know what you’re up against?” says curator Edson Cabalfin. “And that for me is the role of the Philippine Pavilion at the moment, to begin that conversation and to question, then it can move to the revolution, if that’s what the country wants.” Photo by ANDREA D’ALTOE AND PAOLO LUCA FOR THE PHILIPPINE ARTS IN VENICE BIENNALE

Edson Cabalfin, curator and associate professor, University of Cincinnati

At the Q&A during the opening of the pavilion, there were questions that were really pushing for an answer, like what can we do with the points that you’ve raised? And what’s the next step in addressing colonialism and neoliberalism?

The architecture school’s [works] are part of that, Yason Banal’s [installation] is part of that response — it’s not my response. James C. Scott has a book called “Weapons of the Weak” and he was writing about the everyday form of peasant resistances. He said that these resistances do not need to be large gestures. For him, and he had examples of that, he showed these peasants in Indonesia that resisted the large forces of the government in subtle and incremental ways. I’m not saying that the revolution is not necessary. But I’m also very careful that I don’t want this to be about my opinion. If you ask me, yes of course! I think we do need a revolution. But I think we can still do other things that these incremental and maybe everyday forms of resistances [do], which is like the street food markets …

A revolution requires a lot of effort. Look at what happened in 1896, ‘yung pag-assemble ng revolution is a big task. And it has to be organized. It cannot be isolated. But sometimes that is not even possible. I’m not discounting the fact that the revolution might not happen. For me [what] TAO Inc. are doing is great because they’re instituting change in small ways.

I had a conversation with the head of TAO Inc. and asked why there isn’t more participatory design in the Philippines and she said they do train architects for it but once they finish, most of them leave to work in other countries or start their own firms …

Kasi we’re still under all of these forces [of colonialism and neoliberalism]. Kaya kailangan natin maghanap ng ways … If we embrace it and understand what’s going on then we do something.

I did a closing plenary talk at a national convention and after that a lot of people came up to me and said they didn’t realize that neoliberalism was so entrenched and embedded in architecture. So I felt that I was successful in that way because the term became part of the conversation now. If you don’t even acknowledge that it even exists then how can we even fight it, diba?

I always hear this in UP before: Kwestyunin, Hamunin, at Basagin. To question, to challenge, and to dismantle. If you don’t even know what the question [is] then how can you even dismantle it. How can you even have a revolution when you don’t even know what you’re up against? And that for me is the role of the Philippine Pavilion at the moment, to begin that conversation and to question, then it can move to the revolution, if that’s what the country wants.

You’re always asked about solutions to your proposals. Why do you think this is?

People are already very disappointed. And they’re tired that nothing’s happening. That it’s all the same. They’re so hungry for anybody to provide an answer and they will take it. That’s why sa akin, I don’t want to provide an answer because am I already imposing an idea? For me it’s about allowing other people to find answers and solutions. And it has to come from themselves.

“What does ‘freespace’ mean in a postcolonial state with strong undercurrents of feudalism, authoritarianism, and transglobal capitalism?” asks artist Yason Banal. “How is the neoliberal landscape of openness, transparency, and fluidity connected to the market forces, surveillance systems, and creative expressions?” Photo by DON JAUCIAN

Hence the participation of the schools, which was a way to see what people will propose as answers.

Exactly. Because I also knew I don’t have all the answers. I acknowledge that. So I don’t claim to be able to present a solution. Partly, this is my solution, to instigate conversation, but I know that’s not enough. That’s why there’s a call to action. I want people to respond to it, to think about it, and do something about it. It was a very conscious effort for me to allow other people [to join in the conversation] because I was interested in the multiplicity of voices. Kailangan vested ‘yung mga tao, they have to be involved in it because otherwise, just like colonialism and neoliberalism, it’s gonna be imposed on them.

It’s also great that this “humanity” is shown in the day-in-a-life video installations in the pavilion, which show how these built environments are actually lived.

I feel kasi that’s what’s missing. When you talk about the humanity of architecture and that’s also something you should look at, for example, in terms of the way architecture is represented, you have these very glamorous and sexy pictures but there are no people in it. So that’s my response to freespace, you have to highlight the people inhabiting the space, architecture is not just produced by architects because the people inhabiting the space are also creating architecture.

Given all these notions of what architecture is, what forces are impeding progress — and in the course of your research — have you come up with the idea of what Philippine Architecture is now?

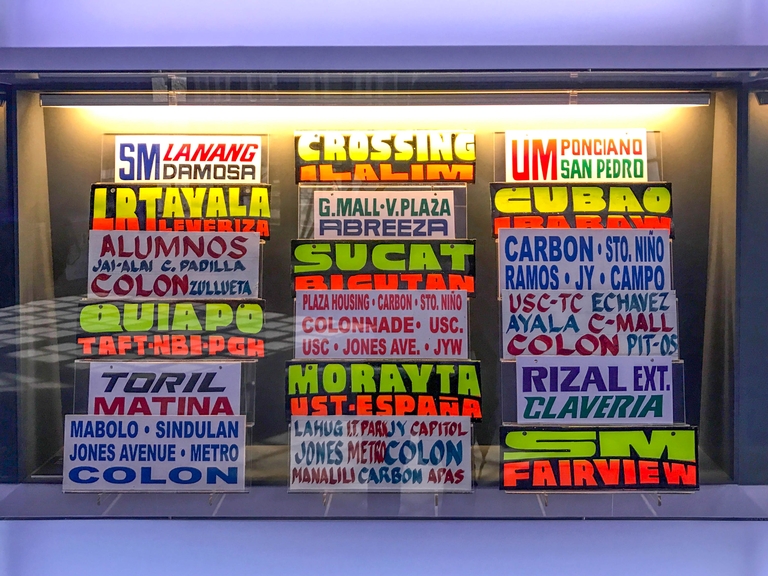

It’s still the definition which I wrote in my children’s book, “What kids should know about Filipino Architecture.”¹ For me, that is how I see Philippine Architecture. Bahay kubo is part of it but it’s not just the bahay kubo. The kariton na nagbebenta ng buko, to the condominium, to the shopping mall. Therefore the practice of architecture does not solely rest on the architect. I want to highlight people in this. Again, just like the idea of freespace is the idea of humanity.

If you look at the Artiglierie, it’s about the stars. But I think Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara also made an effort to highlight other practices that are not known but it’s still about the individual practice. It’s about the practices. Which I purposely did not want to do.

Architecture is not just produced by architects. Somebody made this estimate na only ten percent of the world’s architecture are produced by professional architects and designers. So what happens to the 90 percent of buildings and structures of any kind? That’s why [for me] it was a conscious effort to avoid highlighting just architects. TAO Pilipinas, the schools, that in itself is almost verging on that but still I resisted highlighting this is what the firm did … because they were already producing and given this chance yet students are not given that opportunity to be exposed. Partly, I’m also a professor, I see the power of education to change.

Artist Yason Banal stands inside the pavilion where his multi-channel video installation “Untitled Formation, Concrete Supernatural, Pixel Unbound,” is projected onto the inner walls of the two navels. Photo by ANDREA D’ALTOE AND PAOLO LUCA FOR THE PHILIPPINE ARTS IN VENICE BIENNALE

YASON BANAL, artist and professor, University of the Philippines

What do you think is the worth of joining the Venice Biennale?

There’s always a dilemma and it’s always important to raise those problems and questions and also engaging in them. Like Venice, it’s a canonical exhibition and Western, so it has gone through different translations so to speak, at the end of the day, while the canon is there and times are changing, have changed and new forces are arising, more so the curators, artists, and thinkers and journalists need to engage.

That is how I think about these things, I see myself within and therefore I would rather address the powers that be rather than romanticize my position outside. But I would put my stake [in], I am not an apologist, that’s why I make these statements to put that in that platform and it goes to the Philippines also, that show. We’re also programming films, I’m showing films from the grassroots, showing demolition videos in another month — so I think it’s really how participants approach the project. It’s not the canon that makes something canonical, it’s when its repeated uncritically.

I feel like there’s a certain sense of anxiety in the pavilion, from your installation to the works of the architects in the two navels. Where do you think this is coming from?

Absolutely. I think what’s tricky now is that there’s a lot of righting … these neoliberalisms [were made] way back in the ‘80s. The anxiety that it causes is hard to pinpoint. [What is it like] to be free these days? Before kasi [you can say] Spain, the usual suspects, dictatorships, of course those are to remember, not to forget and revise. But it’s a trickier arena because forces create freedom. And when you’re free you tend to be less empathetic towards the others. Kasi you’re okay, eh.

There is [something] beneath that commodification of freedom and we’re all part of this. It’s hypocritical to say [otherwise]. And to say that the statement of anxiety is a certain awareness that we live in complex times. Complexity is not necessarily depressing which is why I think … anxiety is to be aware of certain darkness and to engage in it, not to be apathetic and to approach it in the work.

How do you make sure that there is enough historical background for the work without alienating the viewers who don’t know enough of the Philippine context?

‘Yun ‘yung interesting when I was making the work, I had so many folders, I went to Bataan, to Pampanga but I was doing a lot of readings, which I also always liked. But the question of how a locality can be translated into something global … and I think ‘yun ‘yung interesting sa neoliberal society is that it almost homogenizes, it almost becomes the human condition. One doesn’t need to be excluded from the other, one can be speaking of a local or a personal so the Philippines situation is not foreign to what’s happening in London, gentrification in Manila to invasion of territories where the state and corporate culture collide, so may particularity.

“There is [something] beneath that commodification of freedom and we’re all part of this. It’s hypocritical to say [otherwise],” says artist Yason Banal on the sense of anxiety produced by the Philippine pavilion. “And to say that the statement of anxiety is a certain awareness that we live in complex times. Complexity is not necessarily depressing which is why I think … anxiety is to be aware of certain darkness and to engage in it, not to be apathetic and to approach it in the work.” Photo by DON JAUCIAN

I think that’s what art does. May local particularities — gender, religion — but there’s something about practice where you acknowledge those nuances because … but then ano ‘yung commonalities, what are these forces? These are forces of empire, forces of corporate culture, forces of fascism. May language na din kasi may history sa buong mundo. ‘Yun ‘yung pwedeng magawa ng exhibition making, pwedeng maging discursive and pleasurable.

What is the importance of having the state be behind something like this? Since it tackles a lot of issues that the state isn’t keen on addressing.

At least for me, the classical notion of aesthetics says beauty, and that’s also been used by neoliberal forces, everything from beauty na aspirational … but I think that’s what art does, like journalism, it forms a check and balance. My being in the university [means] I’m part of the government but that doesn’t mean you are beholden. You love your country but that doesn’t mean your state is the country, and you recognize it yourself.

And the history of the Biennale has had artists [who made statements about the state]… Hans Haacke destroyed the German Pavilion, Ai Weiwei showed his incarceration in [a collateral exhibition in 2013], Mark Bradford in the U.S. Pavilion talked about race … it’s so inspiring to have artists like Nick Joaquin who refused an award or Lav Diaz or Mike De Leon… ‘yun ‘yung nakakabuhay na ‘no, mag-engage!’ and engage in the difficulty because it is the state. At hindi siya antagonistic, it’s being aware of traditions …

The state is an easy suspect. Sasabihin free economy is beyond? ‘Yun ang problematic. We have to look at that and how these two forces are working. Clark is fascinating! You can’t even script that. In one place you have the history of colonization, it becomes a duty free shop selling export overruns with Chinese billboards … that’s it, it’s so veiled. It becomes so abstract. ‘Di katulad dati, alam mo kung Amerikano … that’s why there has to be an engagement.

¹”Filipino architecture is the type of architecture specific to the Philippines and Filipinos. Architecture designed by Filipinos is considered Philippine architecture. When a building is designed for Filipinos, that is also Filipino architecture. When the architectural design helps us to understand the conditions of the Philippines (such as climate, geography, culture, economics, politics, and history), that too, is part of Filipino architecture. Filipino architecture is architecture that responds to the needs, conditions, hopes, and dreams of Filipinos.” — Cabalfin, “What Kids Should Know About Filipino Architecture”

***The Philippine Pavilion at the 16th Venice Architecture Biennale is on view until Nov. 25, 2018 at the Artiglierie, Arsenale in Venice, Italy.