By Sari Lluch Dalena

“How come women are strong in Philippine cinema?” a journalist from Osaka asked during a panel on Women in Philippine Cinema last week, where I sat with fellow filmmakers Sigrid Andrea Bernardo, Antoinette Jadaone, actress Ryza Cenon, and FDCP chair Liza Diño. It was a special panel program on women held during the Osaka Asian Film Festival, giving a spotlight on 100 Years of Philippine Cinema this year.

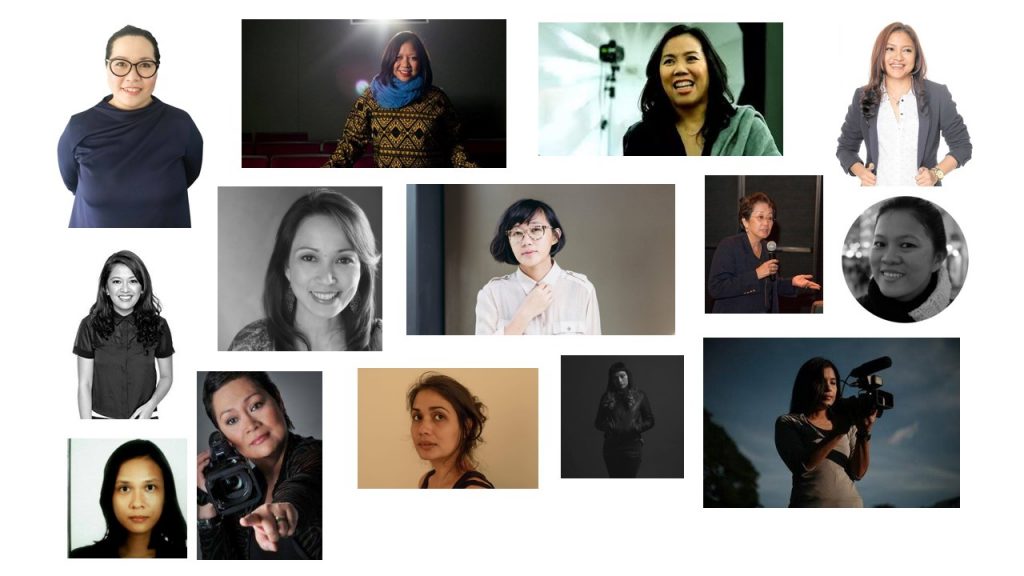

In the last five years there seems to be a significant rise of women making movies in the realm of independent film production. It is a good sign that slowly, glass ceilings are being shattered, but you’ll be surprised when we examine the math showing gender inequality in Philippine cinema:

GENDER IN CINEMA

As we celebrate the 100th year of Philippine cinema, we are bursting with women doing amazing work as producers, cinematographers, screenwriters, and editors, yet there is a gross underrepresentation of women in the director’s chair.

Even in the world of academe, new blood of women film scholars in cinema is lacking. There is also a huge gender disparity in the field of film criticism—males vastly outnumber females in criticism, film selection committees, and jury compositions. These fields remain overwhelmingly dominated by males.

And yes, a hundred years into our cinematic history, there are zero women in the roster of National Artists for Cinema.

This is stunningly ironic. At the UP Film Institute, female students have consistently outnumbered the male students in film studies in the last 20 years. And yet, aspiring female directors face more barriers and lack of opportunities to direct films.

Filmmaker Pam Miras muses, “Personally, I think an equal ratio of films by men and women would take some time to achieve, but it’s not what’s important. What’s important is to create an atmosphere of openness and respect in this industry. To decrease if not totally eradicate discrimination because of factors that have nothing to do with one’s skill in making films—like sex or gender, or regional background, or age, or economic background. And then there is the issue of sexual harassment. We cannot immediately do away with the preference of some for hiring male directors, cinematographers, etc. That took many years and, even in 2018, women in such positions still go through a lot to gain the respect and trust of a 100 percent male technical crew, and even among their male peers. They usually need to be “anointed” by a respected man with the same film role. But I think the Philippine film industry is getting there.”

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Women have been present in key creative roles as early as 1912, when two Americans produced the first full-length film, La Vida de Rizal (Life of Dr. Jose Rizal), the wife of one of the producers, Edward Meyer Gross was zarzuela actress Titay Molina—who, as a director of zarzuelas, might have also had a strong creative hand in producing that first locally produced feature-length film in the country.

Even in those early years we had strong female characters such as Nena, La Boxeadora, played by Maria Tronqued, whose titular character fought in a boxing ring and won to win the prize that would save her from slavery.

Film director Ellen Ongkeko-Marfil reflects, “Such a celebration of Filipina talent might not have been possible if not for our pioneering filmmakers. We’ve listed the likes of Carmen Concha, Consuelo ‘Ateng’ Osorio, Maria Saret, and Rosa Mia, who paved the way for many “firsts” in our 100-year-old cinema. These women broke stereotypes by directing films that were thought to be “macho” and for male directors only. Some of their works presented women in their unglamorized selves—raw, struggling, real.”

The next decades would bring about powerful female producers like LVN’s Narcisa Buencamino-de León also known as Doña Sisang and Regal Films’ Mother Lily Monteverde.

Ironically, despite being in a position of influence, “they, too, are sucked into a chauvinist system that is hostile toward the expression of feminism… All these in order to regain capital and produce profit.” (Nick Deocampo).

“The escape that Doña Sisang brought to Philippine cinema is probably responsible for the heavy escapist hangover that local films still carry at present. She preferred happy stories… She did not like stories that reminded the audiences of their misery.” (Nestor Torre)

“Mother Lily has been responsible for a series of movies that capitalized largely on women who could bare themselves on screen, possessed juvenile fantasies, and had martyr characters.” (Nick Deocampo)

Despite that state of affairs, it was still female directors through the decades such as Carmen Concha, Lupita Aquino-Kashiwahara, Marilou Diaz-Abaya, and Laurice Guillen who challenged the status quo along with scriptwriters Susana de Guzman, Marina Feleo-Gonzales, and Lualhati Bautista.

“In the early years, our cinema generally subscribed to the typical, maybe patriarchal, view of women. As far as my exposure goes, it was Marilou Diaz-Abaya who first challenged the image, status, and condition of women on celluloid through her films Moral, Brutal, Karnal, and Milagros,” Ongkeko-Marfil says of the late director Abaya.

“Many women after Doña Sisang have been running the show,” says producer Coreen “Monster” Jimenez, the one behind the Cinemalaya hit Respeto, “and yet why is it I feel that our stories are still underrepresented?”

“I think the reason there appears to be a representation problem is that we don’t have a female Brocka or Bernal or Mike De Leon,” says director Miras. “We don’t have a female Lav Diaz or Brillante Mendoza, or a female Ricky Lee or Bing Lao. The face is Philippine cinema is still male. The predominant image of the Filipino woman is still one thought up by males.”

DOMINATING DOCUMENTARY FILMMAKING

Perhaps the one filmmaking space that women clearly dominate is in the realm of documentaries. Ditsi Carolino’s films on impoverished slum dwellers, incarcerated children, and farmers, Ramona Diaz’s latest film on motherhood, and Kara Magsanoc’s definitive documentary on Martial Law and the inclusion of the first ever documentary film in the 2016 Metro Manila Film Festival, directed by Babyruth Villarama-Gutierrez, touching on the plight of OFWs in Hong Kong, which was also the first documentary to win the coveted festival’s Best Picture prize, show the spectrum that female directors explore.

Filmmaker Ongkeko-Marfil hopes that women will “make the woman’s perspective—visible, whatever the subject matter—confront the dominant stereotypical view.”

Another aspect of perspectives is that many of these influential women filmmakers hail from the urban middle and upper class. What about the view from the regions outside of Metro Manila? Through initiatives of new grant-giving bodies and even the advent of digital technologies, this norm is also being challenged.

Cebu-based director Ara Chawdhury muses, “the democratization of the practice has allowed a new generation of women artists to embrace the medium and transform how it is created and received in the country. In Cebu, female producers such as Tessa Villegas, Jiji Borlasa, and Bianca Balbuena have revived Cebuano cinema by supporting visionaries such as Remton Siega Zuasola. I also believe that there is a huge opportunity to contribute to the country’s cinematic texture.” This extends even to experimental film where “filmmakers such as Martha Atienza, Kiri Dalena, and Shireen Seno have redefined the way films are created and received in the country.”

THE NEXT 100 YEARS

Assessing the current state of filmmaking, producer Jimenez reflects, “If there is anything I learned in being part of the movie ecosystem, it’s that we need to be in places where our voices will be heard. We need more women writers and directors who would be able to put a piece of themselves in the creation. Our role as storytellers is very important, because movies reflect our narrative as a society.”

This recent encounter with the Japanese journalist in Osaka also shows that, despite their modernity, some of our neighboring countries are in awe of the power of our Filipina filmmakers, who are not just surviving, but flourishing in such a competitive field. Best represented by our longtime “Box Office Queens” Joyce Bernal and Cathy Garcia-Molina to the current queens of a younger generation, Antoinette Jadaone and Sigrid Andrea Bernardo, who are breaking records at the tills.

Film director Jadaone warmly shares, “I think our films will tell more stories on the strength of women, because our industry is in good hands—the FDCP chair is a woman, the MTRCB chair is a woman, the director of the UP Film Institute, the country’s premier film school, is a woman, and the highest grossing independent film is directed by a woman!”

Perhaps director Bernardo’s optimistic view gives the best hope for the future, “I am proud to be a Filipina filmmaker because our industry does not discriminate against being a woman. Our works speak for themselves. We don’t judge based on the gender of a filmmaker. It is this way now because of the brave women who fought for their craft in this male dominated industry in the past. I hope that more women will be inspired to become whatever they want to be.”